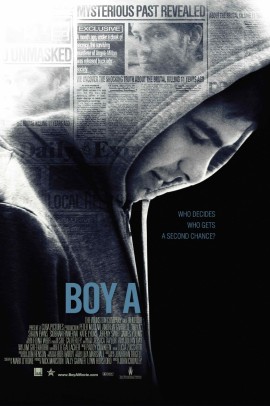

Boy A (2007)

Synopsis

Boy A is a powerful and moving drama about Jack Burridge and his release back into society after serving a jail sentence for being complicit to the murder of a young girl. It is a brave piece of moviemaking that touches on a large array of the themes that I hold as central to my work: The raw and vulnerable fact of human ignorance, the healing qualities of the Feminine, the importance of real male friendship, role models and father figures, and the epidemic destruction caused by our society’s bias against fathers in child distribution cases.

| Genre | Drama |

| Production year | 2007 |

| Director | John Crowley |

| Male actors | Andrew Garfield, Peter Mullan |

Blame it on the boys

by Eivind Figenschau Skjellum

Note: This movie review is not so much pointing at ways to discover our authentic masculinity as it is pointing at the tragic stories that play out in its absence.

Thank you, Terry

Jack is about to be let back out into society after serving his sentence and Terry is the rehabilition worker who is put on the case to make the transition into freedom go as smoothly as possible. In the opening scene, Terry gifts Jack with a pair of Nike Escape trainers. Jack is rendered speechless and with tears in his eyes embraces Terry while expressing a truly heartfelt “thank you”. From this opening scene, we can infer two things: 1: Jack is not the murdering type and 2: Jack has never experienced this level of kindness before.

Jack receives a pair of Nike Escape from Terry.

A strong relationship form between these two from the get-go and Terry refers to him as «my nephew Jack» when he introduces him to Kelly, the woman whose room Jack now moves into. Terry assures him that everything will be okay and ironically a policecar will keep watch over him this first night of freedom. This is not mere nicety from the long arm of the law; as the movie later shows, Philip – the boy Jack was with when they murdered the girl – has already been killed by a lynch mob.

Absent fathers: A recipe for murder

The story is told with intermittent flashbacks to Jack’s childhood, the time when he was still going by the name of Eric Wilson (Jack Burridge is his new identity, taken to protect him from the media and the mobs). We see that his mother is dying of cancer and that his father is not offering much in the way of love to either of them. Although very little is said about him, it is implied that he is a man who is so overwhelmed by the fact that his wife is dying that he has completely shut down.

Eric is a lost and insecure kid. He falters through school, much to the dismay of his female teacher who shames him for not being good enough. When he is out and about, a posse of boys pester and abuse him. And when he finally gets home, it does not present a shelter, for it reeks of death and lost love. Eric has no safe haven in life.

Enter Philip. It is clear that Philip has more of an «evil streak» in him than Eric does. There is something about his eyes, not to mention that he pummels the three kids that have been bothering Eric all by himself. Eric smiles with relief and appreciates that someone is finally standing up for him. A bond between them forms.

On a huge lawn under the blazing sun, Philip out of the blue asks Eric «have you ever been fucked by a guy?» He reveals that he has been raped regularly by his older brother for a long time. At this point, we can conclude that neither of these boys are experiencing a safe childhood, and none of them have had a father figure to look up to. And as research shows, boys with absent fathers, be they emotionally absent or physically absent, are more likely to become criminals. What is soon about to happen is observable in our statistics.

Jack, Chris and the healing properties of the White Whale

Jack is doing well. Terry has set him up with a job for a logistics company where the boyish, but sympathetic Chris fast becomes his closest friend. And then there is the lovely secretary Michelle – «The White Whale». She is a kind and gentle woman and there’s nothing particularly whale-y about her. And when she asks Jack when he’s going to ask her out for a drink, he is left totally dumbfounded. On the other side of some embarassing episodes and challenges and support from his friends, Jack finally does.

What Jack may not be aware of is easy for a trained eye to see: Michelle is a woman with amazing healing qualities. She has an abundance of feminine light, enormous tolerance for others and an incredibly strong nurturing side. She is clearly much more mature than Jack, so why exactly she wants to be with him is a little unclear. I speculate that she awakens in him her mothering instinct. In the deep of her, perhaps she desires to heal him and to be healed in return by the man that will emerge through their love. A good woman knows to appreciate a man with a good heart, and Jack does have a good heart.

I see this dynamic quite clearly for it is not unlike what happened early in my own previous relationship. And just like Jack crumbles in a teary mess on her bosom when he realizes he is loved by her, so once did I (the path to a true and authentic masculinity is often far from macho). The beauty and gifts of the bright side of the feminine are extraordinary (as are those of the dark side, though they require a stronger man than Jack) and they are melting through Jack’s layers of tension.

After Jack and Michelle make love for the first time, Chris and Jack are out on the job, driving some stuff somewhere. Chris teases Jack and seems delighted that Jack got lucky. Then suddenly Jack spots a carwreck on the side of the road. The little girl inside lives, but the man who drove it – I assume it was her father – is dead. The father who is in the driver’s seat is dead. It is quite a symbolic scene.

Chris and Jack are heroes. And while noone knows Jack’s true identity at this point, Jack starts to feel into whether now is the time to come clean, for he has just redeemed himself by saving the life of this girl. He considers speaking out both to Chris and to Michelle, but no songs of childhood mistakes, shattered dreams and lost youth reach their ears. For Terry knows the ways of the world better than Jack and tells him there’s a bounty on his head. Noone must know.

The return of Terry’s lost son

One day, Terry’s son stands on the porch with a small bag in his hand. Terry lost him to his mother when they separated, which we know is relatively normal when couples split up today. The rebellion against the masculine in the last 50 years of our culture has contributed to the idea that mothers are better equipped to raise a child than fathers. Further strengthening the mother’s case in child distribution cases are the emphasis on the idealized beauty of the bond between mother and child as well as the suppressed shadow of the misandric agenda.

And as is well known by those who have studied the evolution of boys, mothers ARE better equipped to raise children – to raise sons – for the first years of his life. But then there comes a time when the mother must take the boy’s hand and lead him to the bridge of adolescence, where the father waits with love and patience, takes his hand, and walks him over to the shore of adulthood. A boy can never become a man without a father, or at least a fatherly figure.

This is little understood by many modern women (I think especially single mothers), which may lead them to energetically feed on their sons and resist with tremendous force their journey into adulthood. It’s natural enough – mothers don’t want to lose their sons – but it’s also selfish and destructive to deny a boy his manhood because you are uncomfortable with it. More destructive still is to use your son as ally, alibi and crutch in the battle against men.

Terry’s son tells him that he doesn’t speak with his mother much. This is a normal reaction when a son has not had a father to take him across that proverbial bridge. The son is still stuck on the wrong shore, struggling to sever the energetic merger with mother he intuits must happen. But he cannot sever it alone, cannot walk across that long and treacherous bridge alone. For the path across is fraught with danger that only a father can fend off, lest the boy run back to his mother every time it gets scary.

So since Terry’s son has not had the chance to take this most essential journey, he has turned into an apathetic and depressed young man. We may do well to understand that the connection with mother is the basis for a boy’s feelings of intimacy and safety, while the connection with father is connected with feelings of value. The son’s feelings of worthlessness are a clear testament to the lacking relationship with his father. Terry is worried.

A monster, dad. A monster over me!

Jack has turned into an object of the fatherly feelings that Terry never got to express with his biological son. He has served as a replacement of sorts after his son’s mother, backed by society, took him from his life. But now, there he is – with mixed emotions: Happy to be with his father and angry that he wasn’t there for him.

There are only losers in this story: A father who didn’t get to see his son because his mother stopped him; a son who is lost in life because his father wasn’t there to guide him safely through adolescence; a mother who has lost contact with her son because he is trying to cut the ties that holds him captive in the prison of his own undeveloped boyhood. This is not mere fiction – for thousands – perhaps millions – it is hard reality.

While having a drinking binge with his son, Terry mutters in a drunken stupor «I love you, Jack. You’re my greatest fucking achievement.» Faced with a father who he feels loves another boy more than himself, the son decides to act. He blows Jack’s cover and everything that Terry has worked for crumbles.

In the scene where Terry confronts his son, some very important dialogue takes place. Terry: «Do you have any idea what this has cost me. Do you have any idea what this has cost that boy?» Son: «And what did he cost me? Him and the others, what did they cost my mum?»

Terry confronts his son after he blows Jack’s cover.

Him and the others. He speaks of men. It is a statement from which we can deduce the following: Terry’s son doesn’t trust men, in all likelihood because he has been poisoned by his mother’s emotional hostility towards them. He now needs a loving father figure to extract the toxin from his veins and to discover his true identity. But since he is so used to identifying with the victimhood of his mother and the bitterness towards his father (and thus all men), he now takes the role of victim himself, rejecting the healing that could be his. Instead of being truly vulnerable, he plays the role as mother’s white knight and the unholy alliance against Dad plays out.

Though it is true – he is in a way a victim, but not of Jack or Terry, but of a society that thinks men are bad and of a mother who refused his connection to the source of true masculine identity by denying him access to father. This is a morally justifiable decision if you can make yourself believe that men are bad, which is essentially what the cultural elite thinks in the Western world. There they go on their white knight missions, destroying and undermining the paths of growth for boys while thinking they are doing them a favour. Make no mistake – they honestly believe that this is a good thing. That is the reality they see. This is why you almost never see a man today who is animating his full masculine potential – society doesn’t want him to (for he will surely end up killing someone or destroying something). This scene is incredibly sad and shakes me up every time I watch it.

Jack is now a fugitive.

Boys: Scum is what you are!

We see the consequence of the anti-male attitude in society in the tragic scene where the girl is murdered. She despises boys, thinks they are scum. She seems to consider girls as inherently better. And since Philip is such a broken boy, he snaps and ends her life, with an unwilling and confused Eric (Jack) as his complicit. It is of course a tragedy that the life of this young girl ends in such a way (and we are watching a piece of fiction), but we must be brave enough to admit that had she not been so aggressive, it would not have happened. She wasn’t quite the beautiful angel she was professed to be in the court proceedings.

Girls often aren’t the beautiful little angels that they are painted out to be. Of course, from nature they can be – they will be – but contemporary society generally has a negative effect on their character, giving them so much special treatment that many end up being self-involved little princesses; narcissistic girls who have mastered the craft of choosing when to be powerful and when to be victim. The suffering they and those around them experience as a consequence is enormous. For this girl, it leads to her death.

It’s not just the girl who thinks the boys are scum. So does the grown ups in the court proceedings. When children who haven’t even hit adolescence are labelled evil, as they are here, we as a society are spreading the disease of irresponsibility. Because it conveniently allows us to sidestep the tough question: Why did it happen?

If we are to move one step closer to truth, we must recognize that human ignorance, fear and woundedness are enormous in our world. We must see that many people don’t have it in them to live life as responsible and ethical human beings and that these people have children. Now we have little people who must find their own way through life, because Mommy and Daddy are not capable of showing them the road. They may be too busy, too shut down or maybe they are simply not that interested.

The result? A generation of lost and/or self-involved boys and girls who try to squeeze happiness out of a world without meaning (thank you, postmodernism). What we’re doing isn’t working. People are hurting.

Conclusion

Boy A is a powerful and beautiful movie. It is also an extraordinarily brave movie, because it shows with such raw vulnerability the extent of the problem that broken father-son-relationships cause individuals and society. And while the armies of the politically correct are not the ones who broke them in the first place (Robert Bly suggests that it was caused by the industrialization of society, where father home for factories), they are supposed to be the ones to set things right. But the politically correct are not out to set things right – they are out to propagate an ideology that places white men as the main culprits of all problems in the history of the world, and women, girls and people of colour as their victims.

That means that, in the worldview of the politically correct cultural elite, as a white man, I am to blame. And if you are a white man, so are you. For all the suffering in the history of humanity. It is crazy and it is untrue. And we gotta speak up about that. For when we don’t, we fail to place the blame where blame is due – the ever-fickle human nature; fear and ignorance in both men and women – and thus we fail to learn from our mistakes. For ourselves and for the Jacks of the world, it is time to learn from our mistakes. And truth be told, even though we may be better off than Jack, perhaps what many of us need is exactly a rehabilitation worker like Terry. A man who can help us find our freedom. Find your freedom.