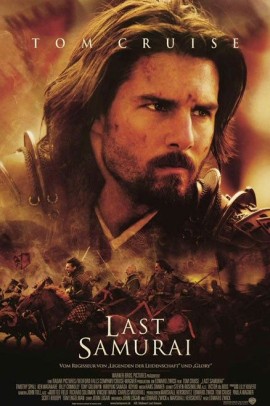

The Last Samurai (2003)

Synopsis

The Last Samurai is an historic epic set in 19th Century Japan. Captain Nathan Algren, hero of the American Civil War and the campaign against the Indian tribes, is hired by the Japanese to quell a Samurai uprising that is holding back the tide of change. Nathan is captured by the Samurai and finds among them the way to end the nightmares that have tormented him so long. The Last Samurai is an exploration of psychological healing, honor, and the time when technology killed the Warrior archetype. Come, the path is clear. Katsumoto awaits.

| Genre | Action, Adventure |

| Production year | 2003 |

| Director | Edward Zwick |

| Male actors | Tom Cruise, Ken Watanabe |

Remembering the time when technology killed the Warrior

by Eivind Figenschau Skjellum

It is 1876, the year of the American Centennial. The American Civil War has recently ended and Japan has begun a gradual opening of her borders to the outside world. Captain Nathan Algren, our protagonist, is a hero of the war and the campaign against the Indian nations. But while his Medal of Honor from Gettysburg is impressive to the common man, it fails to make him forget the slaughter of Cheyenne women and children he took part in under the command of Colonel Bagley.

When we first meet him, he is sat with an anguished look on his face, sweating and drinking backstage at an arms fair. He is waiting to perform his clownish job as poster boy for the Winchester Company. Captain Nathan Algren hates his job. With his mind clouded by alcohol and emotional turmoil, he gives a volatile performance that scares the shit out of the unsuspecting audience, and his existential angst barely contained.

An old associate pops up and talks of great opportunities: Mr. Omura, a wealthy and powerful Japanese entrepreneur, has arrived in America to seek Nathan’s expertise in high-tech warfare. Omura is in charge of the modernization of Japan and needs help to quell a brewing Samurai uprising which is holding back the tide of change.

Japan is at this point in history at a crossroads where age-old feudal tradition is challenged by the unstoppable force of modernization. For a thousand years, the feudal system has existed under the watchful gaze of the Samurai, the elite warriors who served their lords with their life. The Japan that greets Nathan, however, has already been heavily westernized: Japanese in bowler hats walk side by side with westerners, Samurai are eyed with suspicion and angst, and American guns have found their way into the the emperor’s Imperial Army.

It is this army that Nathan is charged with training. He is only, he claims, there for the money – 500 dollars a month – for which, he says cynically to Colonel Bagley “I will kill whoever you want.” Understand and absorb that this is true for Nathan only from his place of confusion. Deep inside, at a core place that the darkness of his conscience has blocked off, he doesn’t feel this way at all.

There is a hidden message here for us: When our minds are clouded by the weight of our actions, we make decisions based solely on superficial gain. Equipped with an untrained mind ravaged by guilt, we are unable to see the greater implications of our decisions. This peripheral vision is required to comply with the golden rule for the mature man: Make sure all of your actions flow within the context of serving others.

Training the Imperial Army

The Imperial Army that Nathan discovers is a ragtag bunch of conscripts. They aren’t skilled with firearms and they aren’t psychologically prepared for battle with the Samurai. Colonel Bagley happily ignores this due to his naïve arrogance and wants them to attack.

The Colonel is an emotionally shut down soldier, a man with no sense of honor, ill-equipped to understand the heart of a true Warrior. Like anyone with little understanding of the inner realms, he puts way too much emphasis on external circumstances – rifles and howitzers over swords and arrows – and disregards the primal force that can exist deep in a man whose actions are in alignment with his higher calling.

Nathan is wiser and reminds Colonel Bagley that while the Samurai may not have modern weaponry, they are elite warriors whose “sole occupation for a thousand years has been war”. Wishing to prove Col Bagley wrong, Nathan challenges one of the imperial soldiers to shoot at him, informing him that lest he complies, his life is forfeit. Nathan has no love for his life and is willing to risk it to prove a point to the man who has caused him so much anguish.

The showdown which ensues ends in slaughter. In a beautifully shot scene, shadows appear from the mist before Nathan’s fidgeting and undisciplined troops. Horses emerge in full gallop, swirling fog in their hoof steps, and the Samurai barrel through the panicking conscripts. After dropping several Samurai, Nathan is captured by Katsumoto, the Samurai Lord he was sent to defeat.

Healing the wounds of the past

Nathan is brought to a mountain village, where he ends up in the care of Katsumoto’s sister Taka, a woman he has just widowed. I am left to wonder why Nathan ends up in the household where they have most reason to hate him, but I think that the wise Katsumoto is lucidly aware of the healing potential in pairing Nathan with the widowed family. It’s also clearly used as a vehicle for the film-makers to show another way of relating to death, one steeped in acceptance, honor, and emotional restraint instead of wild hatred and uncontrolled grief.

Nathan’s recovery from the wounds he has been inflicted by the Samurai is interspersed with scenes from the atrocities he committed against the Cheyenne. The healing process described in these short movie minutes is particularly significant and universally applicable. Consider that in every man’s life, there is an accumulation of a burden of ignorantly or maliciously committed actions.

For the more sensitive, truth-seeking souls (such as Nathan) this burden results in terrible inner conflicts, depression, self-loathing, perhaps even suicidal tendencies. For the more hardened, truth-denying souls, such as Colonel Bagley, the burden is hidden under a hard shell of self-protection, there to be discovered in the unlikely event that the shell is cracked.

It is the man who is experiencing the pain of this burden openly who is ready to be taught, ready to be transformed by life’s lessons. The lances that pierced Nathan’s flesh are the psychological wounds made manifest in his physical body. He has been given these wounds in honorable conflict as a direct consequence of his own actions.

Karmically speaking, the actions Nathan took against the Cheyenne were of such a malicious nature that his own soul has demanded his punishment ever since. This feeling of deserving punishment is, I believe, why he turned to drinking. Only now that the Samurai have blessed him with truthful and honorable wounds does his karma from the Cheyenne start untangling. He can begin to heal.

It is important to extract from this the following insight: When pain and suffering arise in our lives, it is not something that “just happens” to us. Rather, these painful feelings are based on our (un)involvement in past events, and must not to be viewed merely as the burden of life. On the contrary, they are a sacred offering to us, exactly – EXACTLY – the raw material by which our own transformation is forged.

This understanding, when integrated in any man, creates a sense of spaciousness around the pain (which remains) for it is now an ally, the Great Alchemist. This should be a cause of great joy. I ask you, what would this principle mean in your personal life? For Nathan, it means the beginning of his rebirth.

Surrendering to Ujio’s sword

Nathan is not only a prisoner, but a subject of study for Katsumoto and his men. One of these men is Katsumoto’s Lieutenant Ujio. Ujio is a master of the sword with contempt for the newly arrived American prisoner. He harbors a desire to break him and is left frustrated that he cannot do it. There is a scene in which Ujio commands Nathan to put down his sword.

Nathan is standing solemnly in the middle of a village street, clasping onto a wooden sword. The sky has opened wide with rain. Nathan does not comply. I feel here that this scene communicates not just a clash of men but of cultures. Nathan’s culture is one he has come to know as dishonorable, yet it is his culture. And he will not embrace a foreign one, neither as a man nor as a citizen, without a fight.

The outcome is predestined. Nathan gets beaten to the ground, and rises to be beaten yet again. And again. His resilience is the American resilience, but his desire to be beaten is his alone. It is in this painful encounter with Ujio that Nathan begins the surrender of himself to a culture that is not his own. A culture, he may hope, contains promise of redemption.

Perfection in a cherry blossom

“The perfect blossom is a rare thing, you could spend your whole life looking for one, and it would not be a wasted life,” Katsumoto tells Nathan with deep appreciation in his voice as he arrives at the ancestral temple. The previous night, during a theatre play in the village, masked ninjas appeared on the rooftops. Nathan and Katsumoto now have each other to thank for their lives, and their bond as brothers in arms has been firmly established.

By this point in the movie, we have seen the many facets of Katsumoto. Not only is he an elite Warrior, he is a meditating mystic (Magician archetype), a Samurai lord (King archetype), a poet and a clown (Lover archetype). He is all of the four archetypes of the KWML system rolled into one character. He is a true master, a template of masculine potential.

“To know life in every breath, every cup of tea, every life we take. The Way of the Warrior. That is Bushido!, ” Katsumoto insists with fierce intensity and heartfelt devotion as he looks at Nathan. It is precisely this emphasis on life mastery and disciplined observation of the miracle – a cherry blossom – of life, that is missing from the contemporary Western soldier.

It takes no training to kill a man with a gun, but a lifetime of training to deal with the psychological and spiritual consequences. The Samurai believed rifles and other Western arms were dishonorable, because they believed in looking the man you were about to slay straight in the eyes. I agree and have touched on this in my treatment of Lord Of War.

The end of the Samurai, the last Warriors

Inevitably the Imperial Army under the command of Colonel Bagley and Omura faces off with the Samurai on the battlefield. By now, Nathan has taken his rightful place among them and has reclaimed his honor. In spite of his close relationship with Katsumoto, Emperor Meiji has not found the strength in himself to take a stand in the conflict, and Omura has called the shots.

Katsumoto grieves deeply for this, and believes that he is serving the Emperor even as he is preparing to go to war against him. From this I learn that the Warrior archetype is in relationship with only the deepest potential in his fellow man and that he may choose to ignore the words or deeds of his surface meandering. This, I believe, is what honor looks like.

The Samurai put up a spectacular and valiant fight, sending Omura into panic and Colonal Bagley into eternity. But in the end, they are vanquished by gatling guns. Centuries of tradition, lifetimes of discipline and spiritual searching, destroyed in one day by peasants with guns. As Nathan aids Katsumoto in performing his Seppuku, he looks in wonderment at the cherry blossoms, tears in his eyes. His training and honorable ways have paid off and the last words to cross his lips are the words of a Lover, “Perfect, they are all perfect.”

The Imperial Army, understanding what they have done and witnessed, prostrate themselves before the fallen Samurai. This is a very moving scene that is symbolic of the time in history when the Warrior drew his last breath and the soldier emerged as the dominant force on the battlefield. It was the time in history when we buried the discipline of life mastery in favour of dishonorable but efficient technology.

Conclusion

The Last Samurai is no doubt a heavily romanticized portrayal of the Samurai. Yet it does a terrific job of describing a way of life based on a set of core principles, Bushido, that should serve as a foundation for any mature man, even today. It also reminds me of Robert Bly’s insistance on how important it is to give the Warrior the sensibilities of the Lover.

The Warrior and the Lover rolled into one: Europe had Chivalry, Japan had Samurai. Now we have soldiers who end up psychologically traumatized due to the dishonor of modern warfare. Yet, in each of us, the spirit of Bushido lives on, if only as a potential. Nathan’s journey has valuable lessons for the man who is prepared to reclaim what is rightfully his.

There is a Celtic saying that goes something like this “Do not give a man a sword before he has learned to dance.” I have a new saying for you: “Do not give a man a gun before he has found perfection in a cherry blossom.” You can quote me on that if you want.